Mr. Teasy Weasy looking as if butter wouldn't melt in his mouth. Hah!

Mr. Teasy Weasy looking as if butter wouldn't melt in his mouth. Hah!Do dogs have table manners? Well it might be the sort of requirement one would ask of a dog in the Regency. Mine certainly doesn't. Which is what generated me thinking about posting on dogs again. My sweetie-pie demonstrated his lack of table manners on

Thanksgiving at my in laws. After we left the table and were sitting outside on the patio, my brother-in-law leaped from his seat, pointed in through the window. "Is that your dog?"

There was Teaser, like a statue, four feet square in the center of the table checking out the crumbs. And not for the first time. But we in our house have learned never to put edibles on the table without someone there on guard. It took a half a pound of butter and a steak to get the message, but we are now well trained.

However, Teaser is a pound puppy, and didn't arrive in my house until he was six. So we can forgive him. Fortunately, he is small, a Maltese. But I must say, I would not like him to lead my brother-in-laws Golden Retriever astray, especially not on his antique dining room table, which fortunately was still covered by its table cloth.

While people did have dogs as pets in the Regency, and a pug is always a safe bet for this, many dogs were working animals.

I will put up more of the pet-style dogs in a future post, but we should remember that people still hunted their meat, be it animals or birds and they were important to the supply of food for guarding sheep and such like.

The Spaniel is one such dog used for hunting. This 1815 picture is of a Water Spaniel. Apparently water spaniels, and in particular the Tweed Water Spaniel, are the forerunner of the Golden Retriever, which was not a recognized breed until 1835. So no Golden Retrievers in books about the Regency please.

Spaniels were bred to flush game out of dense brush. By the late 1600’s spaniels had become specialized into water and land breeds. The English water spaniel (extinct) was used to retrieve water fowl shot down with arrows. Land spaniels were comprised of setting spaniels—those that crept forward and pointed their game allowing hunters to ensnare them with nets, and springing spaniels—those that sprang pheasants and partridges for hunting with falcons, and rabbits for hunting with greyhounds. During the 17th century, the role of the spaniel dramatically changed as Englishmen began hunting with flintlocks for wing shooting. Goodall & Gasow (1984), write the spaniels were "transformed from untrained, wild beaters, to smooth, polished gun dogs."

Springing spaniels would lay the foundation of all modern day flushing spaniels. In a single litter of springer spaniels, the larger pups would become springer spaniels, the smaller pups would become cocker spaniels, and the medium-sized pups would become Sussex spaniels: Size alone was the only difference.

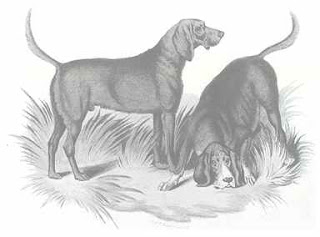

Beagles.

They were used as harriers originally, for hunting hare and rabbit. They used scent, not speed and were followed on foot. Secord's caption to this picture says, "The Beagle, one of the oldest breeds of dogs, is a scent hound developed in England to hunt in packes." I would also find this picture useful to describe countryside and the gentlemen themeselves.

One last dog, then I must go.

Bloodhounds.

In the late eighteenth century, the Bloodhound was used to pursue deer which had been shot and injured but not killed. More chillingly, we are aware that these dogs were used to hunt escaped prisoners.

I think Teaser would be proud if he knew he had inspired yet another post on dogs, but the little rascal's fast asleep under my desk.

Until next time when I will try to find some more interesting dogs for you, Happy Rambles, and may your dog remain under your table.