by Michele Ann Young

Having just returned from Australia, I thought I would share some of the research, and the pictures I took at the Hyde Park Barracks Museum and in the old part of Sydney. I suppose I need a bit of a disclaimer here. I researched information I thought might be useful for a small part of a book I have in mind.

I have not done and intensive study of Australia or the transportation of convicts. This is more like a thumbnail sketch to get me started. I though you might be interested.

I have not done and intensive study of Australia or the transportation of convicts. This is more like a thumbnail sketch to get me started. I though you might be interested.

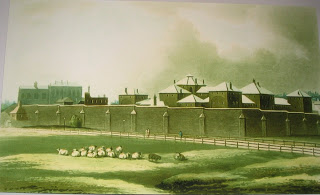

Our first picture is of the Hyde Park Barracks a convict barracks, not military, located on what is now Maccqarie Street in Sydney. It is not far from the famed Sydney Bridge and the opera house. Built in 1817 to 1819, so right at the end of the Regency era. It is one of the few public buildings which survives from that time in New South Wales.

Prior to these barracks convicts were housed in private houses and hotels in areas like The Rocks, an old and less reputable part of town. Apparently, while the convicts were set to work all day, in the evening they had a jolly good old time and got a bit disorderly.

Public outcry led to the building of the barracks for 600 men who formed the labour force Governor Macquarie needed for his public works program.

Francis Greenway, (1777-1837), pictured here was the architect for the Barracks. Born at Mangotsfield, near Bristol, England he was in private practice as an architect when in March 1812 he was found guilty of forging a document. He was sentenced to death, but the penalty was later changed to transportation for fourteen years. He arrived in Sydney in February 1814 in the transport General Hewitt, and was followed in July by his wife Mary, whom he had married about 1804, and three children in the Broxbornebury.

Sentenced to death for forging a document. Good for Mary following him all the way to Australia.

Greenway was responsible for the design of many government buildings during this time, but apparently had few social skills and got on the wrong side of everyone of any importance. I do wonder what he would have thought of the Opera House.

The men who physically built the barracks were also convicts, laborers and tradesmen. The barracks then housed 600 convicts, both government-employed and those loaned out and those waiting assignment. It was not a prison, but it did serve to restrict their freedom and was intended to increase their productivity. While the inmates received basic accommodations and increased rations of food many worked for the government, and thus lost opportunity for private and more profitable and sometimes less onerous work.

The men who physically built the barracks were also convicts, laborers and tradesmen. The barracks then housed 600 convicts, both government-employed and those loaned out and those waiting assignment. It was not a prison, but it did serve to restrict their freedom and was intended to increase their productivity. While the inmates received basic accommodations and increased rations of food many worked for the government, and thus lost opportunity for private and more profitable and sometimes less onerous work.

So there were two kinds of convicts. Government men employed in docyards, stores, gardens, quarries, mines, waterworks, military barracks and in building, lad clering, street and road making or in sydney's brick field or lumber yard. The others were convict servants, or assigned servants, working for private individuals.

Inside the barracks there were plum jobs, constables, messengers, scourgers (floggers) and gatekeepers. those with good behavior were allowed to spend time out of the Barracks after work. Married men with families could live in privat lodgings and report to the Barracks each morning. Some were also permitted to undertake private jobs on Fridays and Saturdays.

After five or so years, a convict could be eligible for a "Ticket of Leave". It must have been a prized event for it allow them to leave the Barracks and find their own employment, provided they remained within a designated area.

Life for convicts in the Barracks and elsewhere was hard. After all, it was a punishment. We'll get to that next time.

Until then Happy Rambles in our modern world.

Having just returned from Australia, I thought I would share some of the research, and the pictures I took at the Hyde Park Barracks Museum and in the old part of Sydney. I suppose I need a bit of a disclaimer here. I researched information I thought might be useful for a small part of a book I have in mind.

I have not done and intensive study of Australia or the transportation of convicts. This is more like a thumbnail sketch to get me started. I though you might be interested.

I have not done and intensive study of Australia or the transportation of convicts. This is more like a thumbnail sketch to get me started. I though you might be interested.Our first picture is of the Hyde Park Barracks a convict barracks, not military, located on what is now Maccqarie Street in Sydney. It is not far from the famed Sydney Bridge and the opera house. Built in 1817 to 1819, so right at the end of the Regency era. It is one of the few public buildings which survives from that time in New South Wales.

Prior to these barracks convicts were housed in private houses and hotels in areas like The Rocks, an old and less reputable part of town. Apparently, while the convicts were set to work all day, in the evening they had a jolly good old time and got a bit disorderly.

Public outcry led to the building of the barracks for 600 men who formed the labour force Governor Macquarie needed for his public works program.

Francis Greenway, (1777-1837), pictured here was the architect for the Barracks. Born at Mangotsfield, near Bristol, England he was in private practice as an architect when in March 1812 he was found guilty of forging a document. He was sentenced to death, but the penalty was later changed to transportation for fourteen years. He arrived in Sydney in February 1814 in the transport General Hewitt, and was followed in July by his wife Mary, whom he had married about 1804, and three children in the Broxbornebury.

Sentenced to death for forging a document. Good for Mary following him all the way to Australia.

Greenway was responsible for the design of many government buildings during this time, but apparently had few social skills and got on the wrong side of everyone of any importance. I do wonder what he would have thought of the Opera House.

The men who physically built the barracks were also convicts, laborers and tradesmen. The barracks then housed 600 convicts, both government-employed and those loaned out and those waiting assignment. It was not a prison, but it did serve to restrict their freedom and was intended to increase their productivity. While the inmates received basic accommodations and increased rations of food many worked for the government, and thus lost opportunity for private and more profitable and sometimes less onerous work.

The men who physically built the barracks were also convicts, laborers and tradesmen. The barracks then housed 600 convicts, both government-employed and those loaned out and those waiting assignment. It was not a prison, but it did serve to restrict their freedom and was intended to increase their productivity. While the inmates received basic accommodations and increased rations of food many worked for the government, and thus lost opportunity for private and more profitable and sometimes less onerous work.So there were two kinds of convicts. Government men employed in docyards, stores, gardens, quarries, mines, waterworks, military barracks and in building, lad clering, street and road making or in sydney's brick field or lumber yard. The others were convict servants, or assigned servants, working for private individuals.

Inside the barracks there were plum jobs, constables, messengers, scourgers (floggers) and gatekeepers. those with good behavior were allowed to spend time out of the Barracks after work. Married men with families could live in privat lodgings and report to the Barracks each morning. Some were also permitted to undertake private jobs on Fridays and Saturdays.

After five or so years, a convict could be eligible for a "Ticket of Leave". It must have been a prized event for it allow them to leave the Barracks and find their own employment, provided they remained within a designated area.

Life for convicts in the Barracks and elsewhere was hard. After all, it was a punishment. We'll get to that next time.

Until then Happy Rambles in our modern world.