For those who comment today, there will be a draw for two copies of The Duke's Daring Debutante, print or e.

When Flowers Wore Shirts by Kathryn Kane

Before I explain the meaning of the title I have given this article, I would like to thank Ann for her invitation to guest here today. I have long been a reader of Regency Ramble and I am honored to be here and have the opportunity to share some of the research which I did for my debut Regency romance novel, Deflowering Daisy.

As a play on the title of my novel, Deflowering Daisy I have scattered a number of snippets of floral history throughout the book. One of those snippets of flower history plays an especially important part in my story. The heroine, Daisy, uses this special technique to create a gift which she believes will raise the spirits of the hero, David, and convince him there is still beauty and joy to be found in life, even if one has to make it for oneself. Later in the story, David, in turn, uses the same technique to provide intense pleasure for Daisy. This particular bit of floral history intersects with the history of dessert.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, some French chefs developed a technique with which to decorate fruit in order to make it more attractive when it was placed on the dessert table. This technique was most often used on small fruits, including dwarf apples, plums, nectarines, cherries, strawberries, currants, raspberries and gooseberries. Fresh, ripe fruit was rinsed and set to dry. While the fruit was drying, lumps of sugar were nipped off a white sugar loaf. The lumps were then pulverized in a mortar and pestle until the sugar was very fine, similar to the granulated sugar we use today. This finely pounded sugar was spread on a plate, platter or other shallow dish, ready for use.

Next, an egg white was separated from the yolk. This had to be done very carefully, for even a small amount of yolk mixed in with the egg white would spoil the final effect. The transparency of the egg white was crucial. At this point, the surviving directions differ. Some call for the egg white to be whipped to a foamy froth, though not so stiff as to create a meringue. But most of the instructions direct that the egg white be used just as it came from the egg, without any whipping at all.

Once the egg white was prepared, each piece of dried fruit would be dipped into the transparent fluid, until it was completely covered. Then it would be rolled in the pulverized sugar until it was fully coated. The pieces of sugar-coated fruit were then placed on a tray, usually lined with a sheet of baking paper and left to dry for three to four hours. The sugar-coated fruit would then be used to make attractive arrangements to adorn the dessert course of an elegant dinner. The pulverized sugar which coated the fruit would catch the flickering light of the candles in the dining room so that it would glitter and glimmer, creating the effect of fruit coated with diamond dust.

This technique was known as fruit en chemise. Translated from the French, it means fruit "in [a] shirt." This technique soon crossed the English Channel to become popular in Britain in the years just before the Regency. But the English did not restrict the use of fruit en chemise to the dessert table. In some of the better homes, fruit en chemise would be found decorating breakfast tables as well.

The English had long loved flowers, and from the end of the eighteenth century, it had become fashionable to decorate the dessert table with arrangements of fresh flowers. Initially, fruit en chemise were incorporated into or around these arrangements, but by the early years of the Regency, English ladies decided to put shirts on their flowers. Though, in most cases, the family chef or cook took the responsibility to dress fruit en chemise, it was the ladies of the house who dressed the flowers. It soon came to be considered another artistic accomplishment for proper young ladies. An accomplishment which a doting mother would have made sure was displayed on the dessert table when potential suitors were invited to dinner.

Only certain flowers would be dressed en chemise. Roses, tulips and other flowers with tightly furled blossoms were not appropriate. Pansies, violets and daisies were all ideal candidates to be done en chemise due to their relatively flat blossom shape. Each flower would be dipped into egg white, then sprinkled with pulverized white sugar. The sugar-coated flower would be set aside to dry, though it was often necessary to carefully shape the partially dried bloom if it had become misshapen during the en chemise process. Once all the flowers were coated with sugar, shaped and dried, they would be assembled into an arrangement for the dessert table.

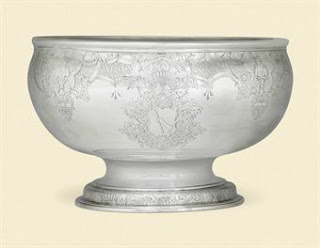

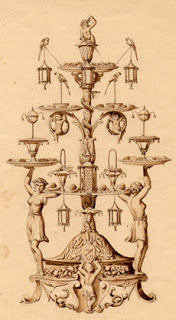

During the Regency, dessert was considered a special course which came at the end of the main meal. The table cloth was typically removed, an elaborate centerpiece was placed on the table and the dessert was served, very often on an ornate china dessert service. Since at least the eighteenth century, it was believed that a beautiful setting for dessert was a crucial factor in good digestion, so dessert was an important final course for any dinner. However, it was especially important for one which included guests, for whom a host or hostess was expected to make every effort for their well-being and pleasure.

Flowers in shirts, that is, flowers en chemise, were considered an artistic accomplishment for many young ladies during the Regency. There are no records that this art was taught in ladies' finishing schools. Instead, it appears that ladies learned the technique on their own, perhaps from observing a chef or cook preparing fruit en chemise, or from their mother or other female relative, who might herself have learned from watching a chef or cook. There may have been at least a few governesses who imparted this skill to their charges as the Regency progressed. In many households, a mother and all her daughters might share in the effort of preparing a floral arrangement en chemise for a special dinner.

Arrangements of flowers en chemise appear to have been fashionable for only a relatively short period, from the Regency though about the end of the reign of King George IV. After that time, bouquets of fresh flowers were the standard decoration on most dining tables. At about this same time, the dessert course was no longer considered a separate part of the meal for which a special setting was required. Not to mention that the steady transition to gaslight would have spoiled the effect of flowers en chemise, since the sugar coating did not glitter and glimmer under the steadier gaslight as it had under flickering candle light.

Deflowering Daisy by Kathryn Kane

Deflowering Daisy by Kathryn KaneShe cannot remain a virgin!

For so she was, after nearly a decade of marriage. When she was sixteen, Daisy had willingly, happily, married a man more than fifty years her senior, to escape a forced marriage to a man she abhorred. Though Sir Arthur Hammond had been a wild rake in his youth, he was so deeply in love with his late, beloved first wife that he never considered consummating his second marriage, certainly not with a woman he considered a daughter. But now, knowing he was dying and that he would be leaving sweet, innocent Daisy ignorant of the physical intimacies which could be enjoyed between a man and a woman, he felt that it was imperative she be given the knowledge which would prepare her for the life of a wealthy widow. Armed with the knowledge of physical intimacy, she would be much better prepared to deal with any fortune hunter who might try to seduce her into marriage for her money. And who better to initiate Daisy into the pleasures of the bedchamber than his godson. David had become nearly a recluse since a tragedy which occurred while he was serving the Crown against the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. Prior to that, his skill as a tender and considerate lover had been bruited about in certain circles. Therefore, Sir Arthur believed that David was just the man to introduce Daisy to physical pleasure. And what might spending time with true and gentle Daisy do for David?

Purchase from:

Jupiter Gardens Press Print

Jupiter Gardens Press eBook

Barnes & NoblePrint:

Nook Book

AmazonPrint

Kindle

All about Kathryn

Kathryn Kane is a historian and former museum curator who has enjoyed Regency romances since she first discovered them in her teens. She credits the novels of Georgette Heyer with influencing her choice of college curriculum, and she now takes advantage of her knowledge of history to write her own stories of romance in the Regency. Though she now has a career in the tech industry, she has never lost her love of the period and continues to enjoy reading Regency novels and researching her favorite period of English history.

For more information about Kathryn and her books visit:

Website:

http://kathrynkane.net/index.html

Blogs:

https://kathrynkaneromance.wordpress.com/The Regency Redingote: https://regencyredingote.wordpress.com/